|

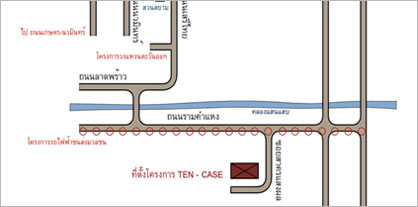

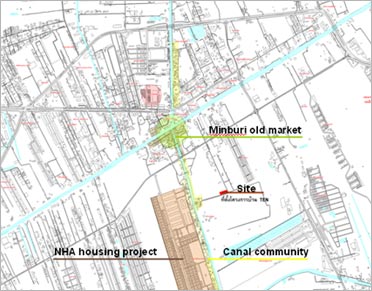

Questions and Significance TEN Bangkok is a housing project that redefines the notion of community and individuality. It offers alternative understanding to both design and dwelling concepts while explores the fundamental relationship between the two aspects. References to context and a sense of place are crucial as it is a project that raises the issue of community identity, relative to individual identity. To what extent can both housing design and dwelling be cooperative? If each and every dweller is involved in the design process, then, at which point does design end and dwelling begin? How can one “own” a place that also belongs to others? Background The above questions are the pretext of TEN housing project. The issue of cooperation between architects and inhabitants have been the focus of CASE, Community Architects for Shelter and Environment, which is a group originally formed in Thailand in 1996 with central interests in alternate housing visions. CASE’s major concern also lies in the relationship between dwelling and context. Both the physical environment and the human element of the place are considered vital to CASE’s housing mentality. In other words, CASE’s aspiration is underlie by economic, cultural and social dimension of the related society. CASE Thailand also shares its vision with CASE Japan, a group formed by similar goal and concept. Both groups are linked by conceptual collaboration, as well as informal exchanges of information and ideas. CASE Japan has been offering housing solutions for those with comparatively less opportunity and choice. Its first systematic cooperative housing project is called TEN Osaka, which consists of ten separate housing units coexisted in the same plot of land. It is the project where the clients are involved in the design process so each and every dwelling unit becomes an expression of their particular ways of life. TEN Osaka has provided a point of departure for TEN Bangkok, which aspires to similar concepts but is founded upon on different methodology and approach. Its goal is to become the unique and alternate housing creator for Bangkok’s forgotten middle class population. |

Problems

While addressing the notion of community and individuality, the project TEN also originated from the current housing problems in Bangkok. The paradox of the Bangkok housing lies in the fact that while most real estate developers cater their products for the high-income inhabitants, it is not the low-income urbanites who suffer from the lack of housing.

Deprived of all types of privileges, the low-incomes are now compensated with governmental aids, resulting in various housing projects across the city. Thus, this leaves us with people that occupy the economic demography between the high and the low incomes. Paradoxically, this has become a group with the most pressing housing problem. While the overpriced housings are out of reach, the people of medium income are also ineligible for the governmental housing aids.

They are forced to enter the deadened route of Bangkok housing, with neither opportunity nor alternative.

With the total provision of upper class housing by the private sector and the governmental aids to that of the lower class, Bangkok’s broad spectrum of middle classes are left with the absence of alternate visions. Thus a number of questions arose.

What constitutes adequacy in housing – is there a bottom line that is not monetary? Is the provision of housing subject, as many other things are, to the flexible and capricious accumulation of capital that characterizes the global economy? What constitute a house these days? Is housing a matter of economy or is it a cultural artifact? If housing is both an economic product that depends on the market economy, and a cultural product that involve the particular ways of live of the people who dwell in it, how can we bridge the gap between the two aspects? What could be the approach?

|

|

|

Alternate Vision As it seems that each and every powerless medium-income individual is left without any housing solutions, TEN began to shift its focus towards the concept of community. What would happen if each of these powerless individual begin to build up its strength through cooperation and collaboration with others. As a collective force, will they stand a chance against the brutal economic stream in the housing world? As an individual each of them remains powerless, but as a community, both their economic and creative power may multiply. Thus, a number of individuals began to form both the ideas and the potential community. |

|

|

|

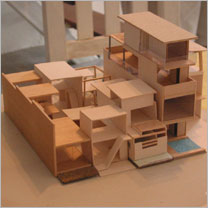

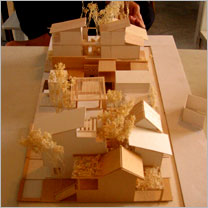

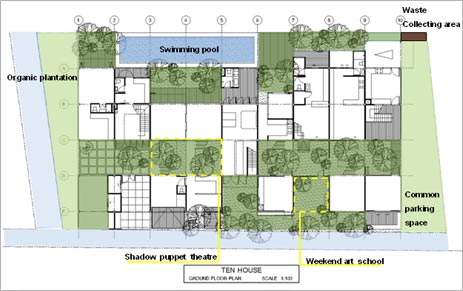

Initial Gathering Initially TEN was formed as a working community of ten individuals who share their vision in alternative housing and ways of life. Each of them is unique, resulting in a group of people in various creative professions, including architects and designers. The lack of buying power and alternate housing choice drew them together. All were in search of their ideal home. They began to draft their ideas and methods. TEN became a collaborative project which would eventually redefine both the concept of dwelling community and individuality, which requires working efforts from everyone involved. Methodology TEN’s working method is collaborative, both conceptually and physically. In terms of the physical collaboration, the project would occupy a single plot of land, divided into ten subplots. The footprint of each subplot is equal. Each inhabitant would then act as the designer of their own home, in collaboration with their neighbors. This method of sharing a single plot of land resulted in the mandatory design collaboration between each inhabitant. Thus, conceptually, everyone involved would have to set their individual and collective design and dwelling criteria. One could not simply insert one’s own design regardless of careful consideration and negotiation with others. Ultimately, each house would conceptually be born out of the site and context, along with other houses. The project would thus consist of various individual dwellings which take into account the notion of community living. Each inhabitant would therefore own a house in a place that also belongs to others. |

||||||

| Individual and Collective Dwelling

Criteria Ten coexisted dwelling unit means much more than ten varying needs. TEN’s unique inhabitants can be understood in terms of both their similarities and differences. Although sharing certain visions, they also differ. They may have something in common, but in details, their ways of lives, dwelling habits and preferences are hardly similar. Thus the question that predicates the design is: to what extent can each and every particular needs, requirements and criteria be fulfilled? And to what extent can each inhabitant conform to the collective living within the community. Thus both the individual and collective dwelling criteria need to be established before the design begins. Cooperative Design TEN does not result from the design of a single creative genius. It is a housing project that each and every unit must be born along with others; each and every design cannot be done individually. It seems that the actual design began after the framework of dwelling criteria was established. Yet, both the design and the dwelling process have already started since the first gathering. Each inhabitant has projected their visions onto the dwelling criteria, which would eventually be translated into design. In other words, each inhabitant begins to dwell within the project even before the actual design started. As they work together to frame the design, the community is formed and the cooperative dwelling has thus begun. Architecture is no longer the familiar cult of objects, which is the product of the architects’ determination and control. Rather, architecture is the fruit of cooperative design where the architects are also the clients; the clients are also the architects. |

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shaping and Re-shaping the Design / Shaping and Re-shaping the Requirements

In the project TEN architecture is longer created according to the requirements of an individual client. Each design is a result of laborious negotiation with others. Therefore each and every design has to shaped and reshaped collectively.

As the design is transformed, the dwelling requirements of each inhabitant are also reconstructed. The result is a unique collective project whose sense of totality is marked by the diversity of each individual design. Cooperative design may work if it also allows individual identity to emerge.

|

|

|

Difficulties As a pilot project, TEN faces various difficulties. Its novelty and experimental nature means that TEN hardly fit any pre-established programs required for most housing projects. Not only that TEN has to establish new relationship with the usually restricted financial program, it also has to reestablish new understanding with both the familiar constructional programs and the existing building regulations. These difficulties have become the creative and productive challenges for TEN. They urge the project to examine all possible alternatives so TEN can become a flexible housing project that is capable of fitting into today’s changing life styles. |

|

|

|

What’s Next?

The ultimate goal of this project is not to serve only a single group of people. TEN set itself up as an experimental project in search for alternate housing vision.

This also opens doors for possibility. It may provide choice and opportunity for those who are sympathetic to TEN working method and concept. Thus TEN would become the provision of housing suitable to both individual requirement and universal application as well as particular location.

A re-definition of housing orientation as well as the relationship between the design and the client, the community and individual inhabitant, awareness of transforming living patterns and changing family configurations may provide the basis for our individual house transformation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|