by Patama Roonrakwit

|

Background Santitham is a small community located just inside the boundaries of Chiangmai City in northern Thailand. Families in Santitham are mostly poor (average monthly income per capita is about US$ 55), and had been renting land there for over 25 years, living in houses they built themselves. The land belongs to a nearby mosque, and in 1995, when news came that a new municipal road was to be built through part of the settlement, the landowner cancelled everyone’s yearly rental contract and asked the people to move out. Sixty two families refused to leave, arguing that they were too poor to afford land elsewhere and had nowhere else to go. |

After a protracted struggle and negotiation process, the Santitham community was able to convince the National Housing Authority (NHA) to provide alternative land for resettlement where they themselves selected the land and secured loans, if they deired, from Thailand’s Urban Community Development Office (UCDO) to build the houses. The agreement stipulated that NHA would fully develop the new land (around 5 acres with 120 plots for Santitham and other communities in Chiangmai that were to be evicted), which was at the city’s periphery, with paved roads, metred electric connections, storm-water drainage and water supply. Each family would be granted individual land title as soon as they repaid their land loans which would be less than US$ 20 per month for a period of 15 years. The only thing left was houses, which the people would have to build themselves.

Early in 1996, I was asked to help the Santitham community to plan their housing design and construction. I first went to the community to talk to the people and get an idea about how they lived before, what they wanted and what kind of resources they had. I found the people very keen about planning their new settlement and houses, but unsure how to build on the 6 x 14 metre plots in the new land, which were much smaller than the roomy plots they rented at Santitham, which averaged around 200 square metres per family.

It can be an interesting excercise for architects to study the housing needs of low income communities, and to then produce ready-made house models designed to meet the needs and affordablity of the poor, based on that research. But “standard” designs produced in this way often end up being scrapped by the poor, who understand their own situation best, and who draw on their own experience and build in their own way, according to what works for them. This is “appropriate technology” at work.

In the early stages of the negotiation process at Santitham, two standard house types were developed by a prominent architectural firm in Bangkok. Both designs looked good to me, but as might have been expected, the people wanted nothing to do with them, and wanted to design their own houses. It is difficult to blame them. So I decided that the best I could do would be to find a way for the architects and and the poor to meet somewhere in the middle and work on the designs together, each drawing on their own expertise and experience. The following describes what happened during a series of evening workshops, held in the Santitham community centre.

|

Getting Started We started the first workshop session by getting to know each other and talking generally about the settlement. People are always shy, especially in the north of Thailand, and so to break the ice, we talked about all the difficulties of making shelter in the city for a family with very little money and no land. How did each family do it, how did people use their houses, what parts of the house were most important, what changes had they made over the years to their houses? I tried to connect all the subjects we talked about to concrete issues of space and function in their existing houses. Then I asked them to draw their own existing houses with their comments about the space and functions. By this time, everyone had already begun thinking about their houses in terms of spaces and qualities which do or do not serve their daily lives. They had begun formulating ideas about what they wanted to keep or to change in their new houses. |

Dream Houses

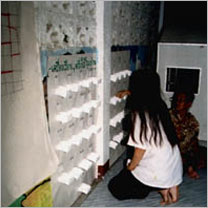

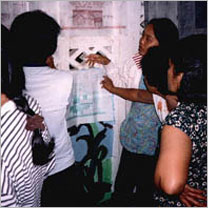

We started the second next session by letting everyone draw a picture of their “dream house”, without worrying about budget or plot size. I found that despite this invitation to go wild, most of the people squeezed all their family’s needs into houses that kept within the limits of extremely modest plot sizes and budgets. We pinned up all the dream houses on the wall. Most of them were very simple - not much more than three-dimensional descriptions of their most basic family needs. No castles, no palaces, and only two houses with tenuous suggestions of a swimming pool or a home-cinema! For me, this made clear that for these people, even such a simple little house is already a “dream”. I asked for some volunteers to explain their dream houses to the whole group, and let the others ask questions. The people all had fun giving each other critiques.

|

|

|

|

Making It Real The next step was to make these “dream houses” a little more real, given the constraints. We gave everybody grid paper and scaled cut-out furniture to stick on. The furniture was to help people get a sense of a room’s scale and to check if the spaces they designed would work. We used the actual length and width of the community centre, where the workshops were held, as a life-size scale, to help people visualize the rooms they were designing at smaller scale. First, everyone drew the resettlement plot (6 x 14 metres) on the grid paper. Then they drew in their houses on this scaled plot, trying hard to squeeze in all the dream house elements and ideas. After that, everybody made rough cardboard 3-dimensional models from these plans. By now there was an element of friendly competition at work, and everybody was trying to make their model nicer than the others.

Risk

In the following session, we divided people into groups according to family size and budget, so people with similar family sizes or budget constraints could borrow ideas from each other and help develop house designs together, more efficiently. After my experience in Songkhla in southern Thailand, I did not anticipate any problems at this stage, but northern Thailand was different - they were unable to work in groups. Group members could not agree with each other’s ideas, each one insisting that their ideas were the best.

|

On top of that, the house-building budgets many of the people had

been working from were much higher than their real affordability,

since many were reluctant to reveal to the group the true extent of

their poverty by stating such a low housing budget. This was a tricky

problem. It is difficult to prepare for an unexpected event and this

is always a risk in action planning method. What we can do is to be

ready for the unexpected. So this time, I was calm enough to ask them

what we should do, since we had only 2 or 3 architects and more than

25 “clients”? At the end, the people gave us the idea of everyones

somehow beginning from the “same structure” but using it in different

ways, according to “different functions”, which the people would manage

by themselves. To us, this idea suggested a kind of modular system. (We had 40 people, nearly half of whom were men. But as the workshops went on, most of the men dropped out, leaving the women to suspect that probably the men considered all this fussing about houses to be something unimportant, too simple for men.) |

Solution

Back in our office, we three architects sat down with the pile of designs from the people. The average size of the largest room was about nine or ten square metres, which could make a neat 3 x 3 metre module. This 3 x 3 metre module could also be conveniently built with and spanned by bamboo, which is cheap and widely available around Chiangmai. So we made hundreds of small cardboard boxes, sized to scale, at 3 x 3 x 2.5 metres, each one representing a single structural unit. These boxes would be the “same structure” and then the “different functions” would be people’s responsibility. Subsequently, using these boxes which we had made as house “building blocks”, the people assembled another set of house models on their grid-paper plots. All the houses were completely different in area, orientation, massing and function. Some houses were small, some were big, some single-floor, some two-floor. The people were all happy with this refinement of their house ideas and were able to explain their house models to the larger group. By this time, we had, more or less, a set of preliminary house designs, based on this 3 x 3 metre module. Next we put the house models all together again, on the big site plan and saw how they all got along with each other. This time we could see much more open space, and could actually imagine living here. Everybody was satisfied with the sense of community that had been created.

|

Community Level Awareness When all the models were made, we laid out a big site plan (same scale as the models) on the floor and asked everyone to put their cardboard houses on the plots. Suddenly, we all had a community in front of us. It looked awful, of course. Almost every house completely filled the little plot. There was no open space whatsoever, one roof drained onto another roof, no place for trees or air circulation. It was packed! When I asked the people whether they would like to live in this community, there was a chorus of unhesitating No’s. Then they started talking about how their new community should be. I did not have to tell them anything, no lectures about density or open space or setbacks. Everyone understood and agreed to leave a small amount of space open on each plot and then went back to re-adjust their house designs accordingly. |

Materials Analysis In the next session, we showed everyone some slides of some beautiful houses built in tropical countries with unconventional materials - bamboo, thatch, scrap wood, cloth. We then gave everyone a simple table in which to list materials and quantities needed for their new house. First they had to see what materials they could salvage and re-use from their existing houses, and then decide what new materials they would need, and how much those materials would cost. The people divided themselves into groups and went out into the city to gather information about the prices of various building materials. When everyone came back, we were able to put together a list of construction materials and their prices - some of which were very cheap. Using plans drawn from the box models and a simple cost estimating sheet, the people then estimated their house costs. I did not have to pursuade anyone to use the cheaper “local materials” rather than the more costly steel and concrete. Some might first have wanted to use those concrete products which are symoblic of middle-class affluence in Thailand, but then they figured out themselves that using these materials would make their houses too expensive. One look at the cost of materials, and families came to their own conclusions. People understand their own limitations, and in this case, reality was the best decider. This does not mean that we are against using concrete or steel, but considering the people’s affordability and the hefty land-loan repayments they will have to be making for many years, it makes sense to avoid deeper debt as much as possible. Gradually, houses can be upgraded, as families can afford to do so. This materials stage of the workshop also gave us a chance to look at construction methods and building processes. The designs were flexible enough to allow people to adopt materials better suited to the construction methods adopted. So, since the people understand how it works to build a house, they will be able to manage to build one.

|

|

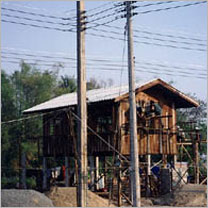

A Case Example The first house designed through this series of workshops was built in the first phase of the resettlement process. The owner, Nongyao, is a woman who once claimed she knew nothing at all about housing design and construction, but the delightful house she built is filled with innovation, cost-cutting creativity and whimsy. She hired a couple of local carpenters to help her, and learned by doing. We came out to the site often and assisted as much as we could. She knew all the details and was able to deal with all problems on site. The overall |

cost of her house was low, working out to about 65 percent of its market price. Later, when people asked me for details and cost figures about the Santitham house designs, I sent them to Nongyao and her neighbours - for advice!